People Are Waking Up: Borders, Invisible Labour, and the Human Cost of Exploitation…

We like to think of our world as global, connected, and progressive. We talk about freedom like it’s universal but for many, it’s a privilege that depends on who you are, where you’re born, and how much your labour is worth.

For some, movement feels like choice: gap years, backpacking, digital nomads choosing curiosity over routine. For others, movement is survival, and sometimes, disappearance.

Borders are at the heart of this contradiction. They are not natural or inevitable. They were created, drawn across history by treaties, negotiations, and power. Lines like the Peace of Westphalia’s recognition of sovereign states and the Sykes–Picot division of the Middle East were political decisions designed to control territory, resources, and people (Merriman, 2009; UNODC, 2024a). These same borders still decide whose movement is protected and whose is policed, sanctioned, or rendered invisible.

In a world with satellites, bio-metrics, and global data flows, people should be harder to disappear than ever. Yet they vanish, not because of a lack of technology, but because what gets seen, protected, and policed is not always human life. It is commodities, markets, and supply chains. Only around 2% of global shipping containers are physically inspected, meaning goods move with flow and oversight that people do not. Meanwhile, the structures that govern labour, migration, and justice often remain blind to, or complicit in, exploitation.

At the core of this systemic invisibility is human trafficking. It is not an isolated crime; it is a structural issue embedded in global inequalities and economic systems. According to the 2024 UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Global Report on Trafficking in Persons, the number of detected trafficking victims increased by roughly 25% in 2022 compared to pre‑pandemic levels in 2019, even as vulnerabilities fuelled by poverty, conflict, and climate change continue to widen (UNODC, 2024a; UNRIC, 2024). The report covers data from 156 countries, the broadest global coverage since the series began.

Children remain deeply affected. Globally, about 38% of detected trafficking victims are children, a figure that has risen sharply over time, especially for girls (UNODC, 2024a; UNRIC, 2024). These are not marginal statistics, they represent real lives being shaped, and often destroyed, by systems that treat them as invisible. Girls are disproportionately trafficked for sexual exploitation, while boys increasingly face forced labour and forced criminality such as coerced involvement in online scams and cyber-fraud (UNODC, 2024a; UNRIC, 2024).

We are confronted not only with the scale of exploitation but also with the voices calling for action. As UNODC Executive Director Ghada Waly has stated, “As conflicts, climate‑induced disasters and global crises exacerbate vulnerabilities worldwide, we are seeing a resurgence of detected victims of human trafficking, particularly children who now account for 38 per cent of detected victims.” She emphasises that “criminals are increasingly trafficking people into forced labour, including coercing them into running sophisticated online scams and cyber fraud, while women and girls face the risk of sexual exploitation and gender‑based violence,” and calls for stronger responses that hold criminal networks accountable and support survivors (UNODC Executive Director quoted in DevelopmentAid, 2024).

This systemic exploitation does not happen in isolation. It is linked to the very way markets operate. Every product we use, whether an electronic device or a garment emerges from labour that is structured by global supply chains. Too often, that labour is precarious, coerced, underpaid, or forced. The cost of convenience, of a tiny rectangle in our hands is often paid in human suffering. We must stop pretending that these realities are separate from our everyday lives.

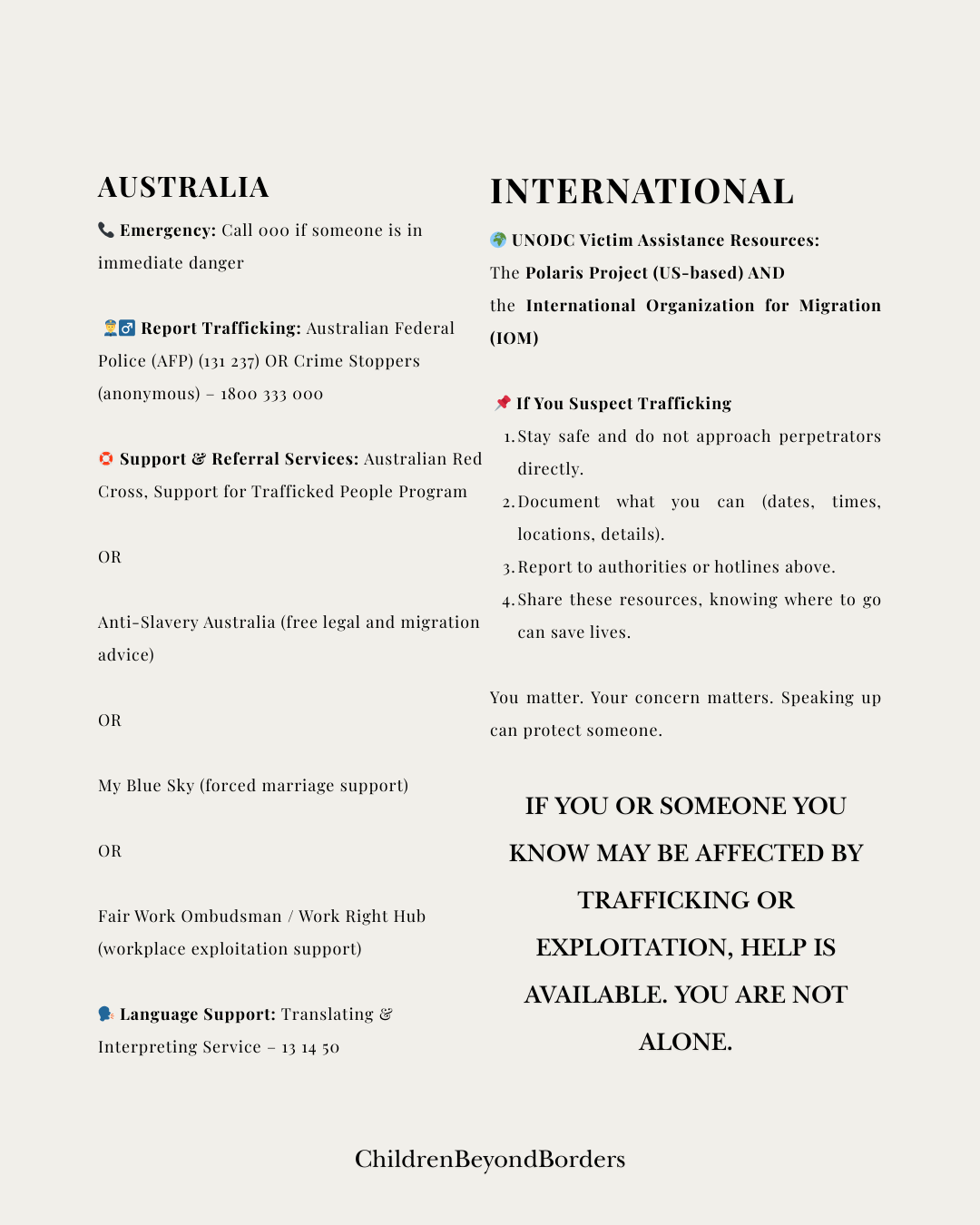

To respond meaningfully, awareness is only the first step. Real change demands structural reforms: robust labour protections, transparent supply chains, effective migration policies that protect rather than punish people, and international cooperation that resists exploitation at its roots. Systems must be built not to hide suffering, but to prevent it.

Freedom cannot be unconditional if it only belongs to some. If it depends on where you are born, what passport you hold, or how market systems value your labour. We are waking up to this truth, reluctantly and painfully, but awakening without action is incomplete.

To stop exploitation, protect human dignity, and safeguard lives, especially children’s we must confront the systems that allow invisibility to persist. Because until every human life is seen, valued, and protected, people will continue to vanish into the shadows of a world that claims it can see everything.

References

DevelopmentAid (2024) UNODC global human trafficking report: detected victims up 25 per cent as more children are exploited and forced labour cases spike. Available at: https://www.developmentaid.org/news-stream/post/189024/unodc-human-trafficking-report (Accessed: 30 December 2025). DevelopmentAid

Merriman, P. (2009) Thinking about borders: Geography, history, and sovereignty. London: Routledge. United Nations

UNODC (2024a) Global Report on Trafficking in Persons 2024 – Trends and Patterns. Vienna: UNODC. Available at: https://unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/glotip/2024/GLOTIP2024_Chapter_1.pdf (Accessed: 30 December 2025). UNODC

UNODC Executive Director quoted in DevelopmentAid (2024) UNODC global human trafficking report. Available at: https://www.developmentaid.org/news-stream/post/189024/unodc-human-trafficking-report (Accessed: 30 December 2025). DevelopmentAid

UNRIC (2024) UNODC global report on human trafficking: 25 per cent increase of detected victims and more children being exploited. Available at: https://unric.org/en/unodc-global-report-on-human-trafficking-25-per-cent-increase-of-detected-victims-and-more-children-being-exploited/ (Accessed: 30 December 2025). UN Regional Info Centre

United Nations (2024) Poverty, conflict and climate fuel spike in trafficking victims: UN report. Available at: https://www.ungeneva.org/en/news-media/news/2024/12/101240/poverty-conflict-and-climate-fuel-spike-trafficking-victims-un (Accessed: 30 December 2025). The United Nations Office at Geneva

World Customs Organization (2023) Global Container Inspection Data. Brussels: WCO.